chapter one

Long ago and far away, on a cold frozen morning in the middle of winter, Peter and Elena awoke from their dreams when the first blue light tickled and called them from sleep. Pinned to their beds by the enormous weight of the goose down quilts, and so snuggled into the soft warmth, they were entirely encased and invisible, great lumps on their beds. The moment the morning sun exposed and subdued the shadows of night, they began to rouse and shift in their subterranean dens. Dazed and dreamy, they squirmed and wriggled, and finally emerged to the ordinary topside world of daylight, filtering through the little moth-nibbled patches in the dark wine velvet drapes, drawn against the bitter chill of night.

“Morning, morning,” sang Peter the eldest, who took upon himself the task of the rooster, cockcrow at day break, which amused and annoyed Elena, no end. No one, he had said, could speak until he had proclaimed the arrival of the new day, as presumptuous a pronouncement as any first born’s under the sway of entitlement. What was one to do with such a brother?

“Hello to you, too,” she said, not quite up to quibble or banter. “I can see your breath when you speak. Mine too.” She puffed and blew and watched her visible breath curl about and disappear. “It must have snowed again.” Peter, interested, threw off the covers and jumped out of bed. Not stopping to pull on his thick wool robe or slippers, he bounded to the windows and pulled open the drapes, a curtain rising on the frozen world outside, on the new dawned day.

Icicles everywhere! A curtain of icicles obscured the far-distanced view, the dear familiar landscape…the large trees near the house and beside the barn, and beyond, the glint of sunlight on water, their beautiful pond, where they swam in the short summers or skated on its frozen skin, one of the few outdoor pleasures of the long, tediously, impossibly long winters.

But whatever gloss there may have been this morning could not be seen. The pond, the barn, the trees could not be seen, because sentinel icicles were in the way, obscuring their view and a cold dazzling sparkle erupted from these suggestive shapes.

“We’re prisoners,” cried Peter. “We’re in the dungeon, awaiting release, for we will be found innocent, at the last minute, and they will have to set us free. The guilty ones will not be able to stand the lies they have told. They are wretched with guilt and will have to go to the magistrate and confess what they have done. And the magistrate will come himself in his black robes and draw out the large key from his pocket and open the door for us. He will apologize and bring us big rolls with butter and honey and strawberries and cream and perhaps a puppy to make up for all we have suffered. But now we are still locked away in our cell and cannot see the trees beyond because the prison windows are barred by cold iron spikes. Come and see them,” he said, interrupting his narrative. “Look how long they are. Like stalactites in a cave, like the ones in our Atlas. How much rain and snow there must have been in the night. Do come and see.”

Elena was still curled up in the covers, raptly following the prison script and imagining the finer points, the exact details of deprivation and want in their squalid hole, empty and silent but for their labored squeaky breathing… how cold and damp it was… and the occasional scurrying of the rat family that shared their place of desolation, appearing to claim the precious few crumbs from the dry bread suppers that the children would be sure to leave their tiny companions.

“Oh, very well,” she said, though she did not really relish leaving the warm cocoon of bed and story. She put on her robe and slippers, because it was too cold and she did not want to catch her death as Mama had warned her. She was as hearty as he, but smaller, and possibly more inclined to mind their Mama. “He must give us hot chocolate, as well, and a kitten” she amended earnestly … “although that would not be convenient for the mice.” Peter, puzzled, looked at his younger sibling with indulgence. “What are you talking about?” But before she could tell him, he said, “Never mind.” He didn’t really want to know. The scene before them was more compelling than anything they contrived.

They stared and stared at the marvelous icicles and puffed their breath at the windows and drew on the fogged surface, enjoying the squeaky music of fingers on glass, Elena began humming a little tune and Peter made a drumming accompaniment by tapping on the window at intervals he deemed musically sound and occasionally stamping his feet. Lost in this dreamy entertainment, they startled to hear footsteps outside the bedroom door. It was Mama, calling them to breakfast.

********************

chapter two

Not that it was much of a breakfast. There were the stewed prunes…again. They had very nearly come to the end of last summer’s dried and preserved plums, the best of their fine orchard. When there were no more, would they really be pleased and relieved or would they miss the tart sweetness that marked the start of each long day? Also there was a porridge of groats. Again. And there was tea, very weak tea. “Sometimes,” said Mama, I think we should have one last gorgeous strong, well-steeped, fully flavored pot and that will be that. But then there will be no more at all tomorrow or the tomorrow after that.” She sighed deeply. It’s just the way it was. They knew how to measure out and make stores last. But the winters were so very long and with the roads closed, no one could go in or out. Some years, the enforced isolation and housebound tedium went on and on: weary, dreary days, dull and monotonous hours when everyone lost sparkle and verve.

“What a pity,” said Mama, “it’s too cold to go out today. It did seem it might warm up a bit, warm up enough to go skating on the pond. That would bring back your rosy cheeks, my pale darlings, and put us all in a better temper.” There is more she would have said, but she stopped herself, not wanting to add more desolation to their confinement. “What shall we do to entertain ourselves?” Her question hovered in the air for a moment, then curled up on the table for a nap.

The children were both lost in reverie, one drawing a sort of horse on the white linen tablecloth with his fingernail and the other pushing the few bits of porridge left in her bowl round and round and round.

The room where they were sitting, where they always sat to have breakfast in the winter, was made cozy and cheerful by the warmth of the pleasantly crackling and sparking logs blazing in the hearth. Mama opened the carpet bag at her feet and drew out the roll of canvas, which she was ornamenting in colored wool, with which she planned to cover her favorite armchair.

Looking up to see what their mother was doing, the children excused themselves from the table, idled over to the windows and looked out at the frozen world, pining for activity, longing to be out of doors, to be themselves among the trees and amidst all the other creatures who lived and thrived in wilderness, in the open, where anything may happen, where something usually does. Just to be outside was happiness. The experience of wind on skin…gentle breeze or a strong buffeting gust… was pleasure, the smells of forest pine or garden rose, intoxication, and a nest of hatchlings, a trail of ants, excitement and adventure. They needed no other entertainment or amusement out of doors. This was the whole of life to them and they lived in an eternal present, moment to moment, rapt and fulfilled.

“Oh, Bother,” said Peter, striking and stroking a forceful swathe down the heavy claret drapes that encased the windows and a clot of dust emerged which excited a momentary display and diversion when the tiny particles swarmed, billowed and disappeared. Elena coughed a bit and punched the drapes on the other side to achieve a similar effect which naturally provoked Peter to repeat with a greater flourish and impact, and so on, until the two children were pummeling, and dust was spewing, and old Felix, their aged wolfhound, whom Papa had thus named for a joke, looked up from his post near the hearth and began to howl, taking up their excited jabber with his doggy complaint.

Mama said nothing until the sound of old fabric tearing stopped the frenzy. “Children,” she said, “You need exercise.” She put down her needlework. The tiny stitches with which she was working the pair of thrushes on a blossoming branch were beginning to tire her eyes and the sound of the children’s entertainment addled her concentration. She stopped before the drooping drape and examined the fray, estimating not so much the damage but the time and thread it would take to mend the rent. “Well,” she said, “it’s not too bad, you know. And it will be a break from the needlepoint.”

She took each child by the hand and walked them towards the door. “Now,” she said, dropping their hands. “Make a line and follow me.” She began to march briskly through the halls and corridors, up and down the stairs, lifting her arms straight up, then bending the elbows and touching her shoulders, then dropping her arms to her sides. This exercise she repeated continuously, keeping up the brisk pace until they all became quite breathless. And as they snaked through the house, everyone’s breathing could be heard among the squeals and bits of songs and poems they chanted or shouted, when a familiar remembered line matched the rhythm of their marching.

“Morning bells are ringing. Morning bells are ringing.

Ding, ding, dong. Ding, ding, dong.”

They ended in the kitchen where Aunt Marta was chopping vegetables: potatoes, parsnips, and beets, the root vegetables that kept them through the winter, as well as cabbage and onions which she sliced for the big pot of soup she was making for the family’s dinner, that simmered all afternoon on the big stove in the kitchen, the warmest, most pleasant place to be in all the wonderful house. This was always so, not only this time of year when warmth of the snug room was most welcome, but in any season when the enticing aroma of Marta’s soups and bread made one glad to have an appetite. Aunt Marta practically lived in the kitchen and she was happy there, if singing were any indication. If she were preparing a chicken, she sang in a quiet, melodious voice a song of many verses, improvised, most always the same, each variation depending on whatever ingredients accompanied the bird to the oven. She sang while singeing and plucking its feathers, sang while firmly removing the giblets for her sauce or a paté she made with its liver chopped with onions and hardboiled eggs. She sang when she was bathing the insensible fowl, while patting it dry and rubbing it with salt and pepper, explaining how delicious it was going to be with celery, carrots, onions and garlic. And it would be.

She was very fond of the children and their Mama. And their Papa too whom she had known his whole life and about whom she also worried. She said her prayers for him and kept him in her heart which was roomy enough to contain them all, though there was reserved a singular place for her cherished sons who died in the last war, both of them, haplessly… as so many young men had… and not so very long ago. When she thought of them, she took to sniffing and rubbing her eyes.

Not wanting anyone else to bear her sorrow with her, she attributed her sniffing and blowing into a voluminous handkerchief to the cutting of onions. Pavel knew better. If her husband came into the room when she was cutting onions, he put his big arms around her and gave her a squeeze. She smiled just seeing him. That they were still so dear to each other after so many years together! Sometimes the kitchen pealed with their laughter. Pavel may have lived a long time, but he retained his youthful playfulness and physique. He, like many contented men, liked to tease, play harmless tricks and make jokes, finding humor even in incidents and circumstances others considered too serious or sanctified.

Pavel spent his days outdoors or in the barn where he had his wood shop. The family’s caretaker and Jack-of-all-Trades, he always had something to mend or make. That’s how it is in the country…things weather and break and must be repaired, a part or two replaced. And as he was an inventive sort of person, he enjoyed using his wits. He was never at a loss for what to do. The family had a cow, Zoya, and it was Uncle Pavel who milked her twice a day, it was he who fed and also talked to her. He loved her as well as everyone else in the household, believing her to be a part of the family.

He was also a gardener who could coax seeds, those tiny specks of possibility, to grow into large and flavorful vegetables. He stored the root crops in a shed, providing their meals in the long stretch from last harvest of autumn to first harvest of the new year. He pruned the orchard at the thaw before the sap of spring awoke the trees and gathered their fruit in bushel baskets when they ripened.

Aunt Marta and Uncle Pavel were not actually the children’s aunt and uncle, but so long a part of the family and so adored, they were affectionately considered so.

********************

chapter three

In the mornings, Peter and Elena worked their way through sums, read Botany and copied drawings of herbs and flowers in notebooks with heavy paper that could absorb their ink. They each had permanent stains on the insides of their index fingers where ink dripped from their straight wooden pens. They dipped their pens in an inkwell over and over as they drew and wrote. Sometimes they forgot to discharge the excess ink before lifting the pens which dripped and dribbled everywhere. But they were learning and grew more skillful every year. They studied history or spent their time declining nouns and conjugating verbs in Latin or memorizing, say, the pluperfect tense in French. They had to have studied before they had lunch and were released to their own inclinations. They spent the afternoons reading for pleasure. Sometimes Mama read to them and sometimes they took turns reading aloud, which was not nearly as satisfying, but better than not reading or privately engrossed in their own stories. They liked to hold onto a narrative in common, to share exploits and adventures, excitement and danger, daring risks undertaken by the noble and bold. They admired and threw themselves into the lives of heroes willing to stick out their necks for a good cause. Like children everywhere, they gloried in tyrants vanquished, cruelty punished, good deeds rewarded and obstacles overcome. Today they were entirely absorbed in reading The Three Musketeers while Mama was off somewhere else… in her own room, as it happens.

In her boudoir, she was lost in musing. If only, if only Papa weren’t away. She didn’t like to consider the hazards of war. She simply missed him, his big bear laughter, his joyous disposition, his bright geniality. How he filled the house with laughter…. She sighed deeply and walked into an alcove where his books and notebooks were shelved and ran her fingers along their spines imbibing sense memory of him, not nearly enough. They hadn’t spoken of him for days, but he was always there, a presence felt, missed, and longed for. There was no mail, there hadn’t been, there wouldn’t be for many more weeks to come, until the snow melted and carriages could get through. She reached up to the highest shelf and brought down her treasured box of letters. She carefully untied the delft blue ribbon that bound the little packet of notes he had sent and regarded the crisp cream paper and his dear legible hand.

She read them again, one by one, laughed at his jests and felt the gladness of knowing him fill up her heart and dispel the sadness always lurking beneath her attention. Anything…a favorite melody, the cast of light in a room, the children’s features…could remind her of him, of their lives together, their happiness, and the jagged edge of his absence tore through her. But for the sake of the children, for their future, the resumption of their ordinary lives, she resisted the temptation to blow away in the squalls that sometimes beset her. She kept their ship afloat with equanimity and good humor, buoyed up by the daily happiness she found with the children in the pleasures of small things.

“What’s this?” she said out loud, holding up a letter written on different paper with a strange yet vaguely familiar hand writing. She scrutinized the missive with her entire attention, but still unable to discern the sender through comment and script, she turned the page over and looked to the signature to find the name of her cousin and childhood playmate, her cherished kinsman, Nikolai. She read as if for the first time. Preoccupied as she was with her absent husband, she must have set aside his note for a later reading and then forgotten it. Poor Nikki. She failed to exchange his message with one of her own. They had always been close and grew closer over the years through their correspondence and the distance that separated them, since her marriage and the move up north to her husband’s manor. Dear man. What had he written?

My dear Vera,

I think of you often and wonder how you and the children are faring without Leo. The winter will undoubtedly be long and arduous, especially for the children, without at least a sleigh ride with Papa to look forward to. I have been thinking about how dull the days will be for them in the middle of winter with every game played, every book read, and every indoor idyll already accomplished. I still remember the tedious winters of our childhood which weren’t nearly so trying. Do you remember the air so cold it was hard to breathe, even through mufflers, the beads of ice that collected on the wool, how long it took our mittens to defrost? How hot and red our legs were when we finally came inside and Aunt Lena or Mama drew us each a bath to warm up again.

I remember how bored and cranky we became as the nights lengthened and the time we had outdoors diminished and disappeared. So I know how your children feel and I want to bring sweetmeats and toys to amuse them

. I have business in Aleppo this autumn where I’ll find dried figs and dates, candied citron and the little cakes made of pistachios and honey they love. That should sweeten them up. I have been busy carving. I won’t tell you what. I want to make a surprise. Know I’ll bring a keepsake for you, too, dearest Vera. Look for me at the time of the solstice. I shall try to get through.

As always, your Nikki

But he hadn’t gotten through. It was long past mid winter and the roads were impenetrable. Sometimes, while walking through the house, she thought she heard something and stopped to listen. Several times she flung open the door only to be smacked by the chill of swirling snow. There was nothing, just the wind.

Still, she felt such a stirring, thinking his arrival imminent, his presence about to fill up their lives with overflowing gladness, the simple happiness of being together. Really, she felt something out of the ordinary and yet…. She debated whether or not to tell the children of her premonitions. She didn’t like to raise hopes bound to be dashed in disappointment.

Still, she felt such a stirring, thinking his arrival imminent, his presence about to fill up their lives with overflowing gladness, the simple happiness of being together. Really, she felt something out of the ordinary and yet…. She debated whether or not to tell the children of her premonitions. She didn’t like to raise hopes bound to be dashed in disappointment.

She would write Nikki and ask if he planned to try again next year or if had resigned himself to accept the harrowing conditions of northern winters. Really, she missed him. He must come to visit them, but how? He traveled in lands to the south when the weather was fine, when the roads and market places were open along the roads he traversed, buying and selling foodstuffs. That was his business, his life. Who in his right mind would travel in the cold and dark, bleak and stormy time of year, the dead of winter, to make a social call? Oh, but if only he would. If only he could.

********************

chapter four

He hadn’t gotten through…though he had tried. In Autumn, he started out when the air was crisp and clear just after the settled snow had fallen and remained. It was decidedly dry and he speculated, he wanted to believe, that it would be one of those virtually dry years when, well, when the roads would be open late because of a break in the regular pattern and habit of winter: early, hard and long. Wasn’t the lake late in freezing? The streams and rivulets that coursed through the woods in early spring were still flowing. Perhaps. He just might. But…he wondered at the folly of …what he contemplated.

Honestly, did he think he could slip through the eye of a blizzard and through the high forests without obstruction? That the guardians of the gate would let him attempt the impossible without obstacle and impediment, just for the wish? He knew there would be Peril. He shivered involuntarily at the possibility, no, the certainty of such a prospect, but he was determined to go, keeping his Godchild and her brother foremost in his thought. Besides, he told himself solemnly, such a journey promised to be an Adventure.

All through the ages, youth of romantic temperament and keen disposition aspire to great deeds. Nikki was no exception. He gravitated toward heroic acts, to feats of derring do. Nothing else mattered quite as much. Business was good and even interesting, but business was business. He had never been able to give himself entirely to buying and selling, bettering his lot. Not that work isn’t useful and necessary. Everyone has to earn a living. Still, he found this an insufficient bargain with fate. The market seemed a paltry substitute for real occupation, the kind of arena he longed for, where one’s entire being, one’s mettle, is tried and tested, where he could pit his endowments, fortitude and will against circumstance and chance. He was inclined to hazard all, even his own life, if it came to that. Yes, he yearned for a quest, a generous deed. He was ready to seek his fortune and learn the meaning of Valor and High Adventure.

Such had been his musing before he packed and provisioned the sleigh, including feed for the horses. He wrapped grain in thick cloth, making bundles to fit in everywhere, taking up most of the space. There was room for the sweetmeats and toys he was bringing the children and the gift for Vera, a splendid hourglass he himself had made. He worried that such a gift might distress his cousin, biding time, awaiting Leo’s return.

But then again Vera loved beautiful and useful things. She wouldn’t go to pieces receiving something that reminded her of Leo, however long absent and sorely missed. She was reasonable, not sentimental. As a child, she grieved the deaths of favorite pets, but not excessively. Well then. He would bring the hourglass. For himself there were pickled cucumbers, cheese, dense loaves of rye, dried apples and prunes. He packed a fur rug to keep him warm during the long run. He left his affairs in the capable, he was almost certain, hands of his younger brother, Arkady.

Early on a Monday morning after the first new moon after the harvest, Nikki dressed in his warmest clothes, leather breeches and wool sweater, cap and mittens knitted by his childhood sweetheart.

Tasha was determined to shelter him from the elements, as well as she could. If go he must, warm he would be. She chose the brightest crimson because he would then be visible in a blizzard. Even the weighty sheepskin jacket she constructed, she tinged with bright dye. She wished the weather clement, hoped storm would not obscure or engulf the way.

And so while knitting and stitching, she wove in prayers for his safekeeping, a fortuitous end to his difficult journey. Really, she wished he wouldn’t go, but Nikki was Nikki and once he made up his mind, there was no unmaking it. She hummed while she worked, in a kind of woolgathering dreaminess, as if entranced by the rhythmic clicking of the needles. She was confident her spells were binding…not because she was a witch, not because she was deluded, but because she loved him. She wanted him to come home to them, alive and whole. There had been too many dead heroes in the wars, too many sweethearts, mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, sons and daughters left bereft. “Enough,” she advised herself, seeing the slippery slope of her thought, but wishing in spite of her caution: “If only women could stop men from slaughtering themselves in war.”

Nikki continued his preparations cheerfully, whistling and singing as he worked, stopping to take in the dear face of one and another of his kin, fixing them in his mind for company on his solitary drive. How the family had teased when he tried on the finished clothing. Cousin Sonja squealed when she saw him and asked between giggles: “What is wool from top to toe and red to boot?” “I know. I know,” said Stepan. But he didn’t. No one could guess and Sonja admitted, blushing, that there was no point to her riddle. Teasing and laughing mitigated worry. Who could gainsay Nikki ? Who could dissuade him from this foolish foolish errand?

Only his father articulated misgivings. “Where will you shelter yourself and the horses? What if a blizzard or misadventure…or wolves…or bears…? He left the question hanging in the air like a stalled kite, unable to sufficiently and convincingly portray the dark peril he could only surmise, never having ventured out or been lost in a storm, never exposing himself to danger if he could help it, a careful man with so many depending on him. Father wanted to forbid his son to go. How could he consent and so consign his dear boy, to who knows what danger, what fang or claw oblivion? But Nikki was of age, a man, so there was no forbidding to be bid. Despite the compelling arguments, Nikki was adamant. He was not going to abandon his dream, his deed, his manly chance. There were Vera’s children. He remembered their childhood when they lived together farther north, though not as far north as Leo’s manor. He remembered being insulated and stale…no proper state for children living moment by moment, in an eternity of now. Other fathers’ sons were sent to battle. No one objected then and war was infinitely more dangerous…and destructive.

The morning of departure, the family assembled around the sleigh to embrace their darling, to give him messages for the family far away, bringing well-wishes and admonitions. “Don’t travel too long each day or you will tire yourself out.” “Feed the horses only a little in the morning so they won’t be sluggish. Give them more at night, so they’ll sleep with full bellies.” “Keep your cap on and your head warm even at night, when you are sleeping.” “Don’t let your feet get cold or wet.”

Nikki’s mother brought plum brandy for Vera and some for himself as tonic, to fortify himself when he grew cold and tired. His sisters Anna and Clara baked seed cakes for him and Tasha carried strings of silver bells which she tied to the horses’ harnesses, the way Swiss people tie bells to their cows, so when they wander off and get lost, they can be found. “One last gift and wish,” she said, drawing from her pocket a smooth stone minutely and faintly etched with horses’ heads. Oddly shaped and worn at the edges with a small hole at the center, it was to be their guardian Talisman. “St. Vlasia will protect Vania and Galia.” She kissed the stone and gave it to him. Then she pulled him close to her and buried her face in his neck and kissed him many times with great tenderness. She told him to return to her in the spring when the roads were open and the land would soon turn green. “Be careful. Come home.”

It was a beautiful clear morning, not too cold, and Nikki’s father remarked what an auspicious beginning for the journey this was. Nikki’s sturdy young Steppe Hound barked and barked, an overgrown puppy with many names: Smetana, because she was the color of sour cream, Sobaka because she was a dog, and Laika, mainly Laika, because she liked to talk. You could put your hands around her muzzle, look into her eyes and tell her to be quiet and she obligingly barked her assent as soon as you removed them. This morning, sensing the palpable undercurrents of excitement with her quivering nose, Laika started barking and running around the sleigh which caused equine ears to twitch, manes to shake, bells to jingle.

And thus it was that Nikki mounted up to his place in the sleigh, to the little bells’ merry trill. After a few more take cares and Godspeeds, the horses lurched forward, clip clop, and stepped backward, clip clop, to gain momentum, then forward again with a quickly accelerating pace, and off they went into who knows what, accompanied by Laika who took the lead as if she knew exactly where they were going. The rest of the family scrambled up the hill to the highest vantage point to watch and wave until man, dog, horses, and sleigh became a little dot on the horizon and, like the sun sinking into the rim of the world at day’s end, disappeared.

********************

chapter five

For a long time, Laika stayed with her master, running abreast of the sleigh. She would not leave, however firmly and persistently Nikki commanded and implored. She strode and loped and kept up with the horses’ trot hour upon hour, barking as if she did not understand the words: “Go Home! Go home, you foolish hound. Already it is such a long way back. You will be too cold and tired. You will not like it tomorrow when everyone else goes for a walk and your paw pads are sore and your joints stiff, when you will be too weary to get up even for your dinner. Go home right now, before it’s too late!” He might just as well have said: “Feign indifference,” because she ignored every address, though she barked right back when he spoke, still running and breathing hard, her pink tongue lolling, her eyes keen, her whole being filled with the pleasure of exertion, out and about on a glorious run.

At last, when Nikki noticed she was limping, when he saw she would not turn back, he invited her into the sleigh, onto the seat beside him, accepting her faithful presence and fellowship. Laika jumped in, wriggling and squirming until she made a place for herself against his warm leg, thumping her tail agreeably, whimpering her thanks and looking at him adoringly. “We shall keep each other warm, at any rate,” said man to beast, which she undoubtedly knew all along. Better to live moment to moment as children and animals do, in an innocent reality unclouded by should or ought. How much better two snug in a sleigh enjoying companionable warmth.“Well, I will have to make you a partner in this expedition, since you seem to know better than I what is good for me.” Laika barked and thumped her tail in the confined space that was now hers to occupy. The hoses’ bells jingled and they trotted ever onward.

Night came on, not gradually as you might think, but all of a deep dark sudden, the sun disappearing into a veiled indigo sky. There was a sliver of moon intermittantly obscured by dark clouds massing and vanishing into the gloaming. Without the North star for beacon and guide, Nikki was hard pressed to find a layover. Unattainable now, they would reach an inn several versts to the north tomorrow. Tonight, they would have to stay warm through exertion and the aid of an obliging providence. They stopped by a little thicket that seemed friendly enough, the deciduous trees rather naked with only a few leaves covering their limbs.

Nikki climbed out slowly, rather creakily for a young man, and did a number of knee bends to stretch his legs. Laika, now rested, sprang from the sleigh and she too stretched before investigating their surroundings, sniffing everywhere and barking her findings. The horses shook their heads and the bells chimed, a lovely sound in the quiet of the still and silent night. Nikki unhitched and walked them away from the sleigh. Then there was a scramble to find enough wood to make a fire and enough light to find branches and logs, to make more heat. Nikki scraped away the leaves in a little clearing and heaped up dried moss for tinder which he surrounded by twigs. Then he piled on larger and larger sticks and took a silver box from his pocket, removed a match and lit the fire. Once it was burning well, he resumed his gathering.

A small wind arose, riffling the blaze. Laika fetched some sticks, dropping them at Nikki’s feet, retaining one to gnaw when she finally settled, circling the spot several times before alighting. Nikki rubbed his hands together, enjoying the flush of feeling return to his cold fingers, then hunkered down next to the fire a moment to warm himself through. She barked when Nikki paused to scratch her ears, reminding him to feed them. She barked again and Nikki rose, walked back to the sleigh and retrieved a bag of grain for the horses who whinnied and snorted. The familiar sound of their chomping was comforting. Then he fetched a jar of water and poured some into a bowl for Laika who lapped it right up. He opened a packet of cold meat for his supper and gave her some.

After they finished their meal, Nikki built up the fire to make a strong blaze and a lasting pile of embers. Man and dog retired to the sleigh to tunnel into the warm rugs and blankets where they fell fast asleep, dimly aware of the howling in the distance. Laika raised her head and growled, then slept again. Wind or wolves? Nikki wondered, but couldn’t stay awake.

********************

chapter six

How it had snowed, not so much that the road disappeared, but enough to require vigilance. The horses shook off the snow clumping on their backs and Nikki dusted off occluding bits from his lashes and brows. Twice they had nearly gone off in a gulley and once he had to stop to get his bearings in the oblique glare of sunlight bouncing on the gleaming snow. The sun glinted on the face of the compass he held in the palm of his red mittened hand and he made a tent over his eyes with the other to keep the blinding light from obscuring the directional arrow. “ So soon, so easily amiss,” he sighed. But he needn’t have worried. The compass confirmed they were right on course.

By the time they reached the inn next evening, man and beasts were worn out. They had broken camp at first light to get an early start. Even so, the Inn was farther away than he remembered. The plodding horses snorted, their loud breaths forming evanescent plumes. Evening frost formed crystals on harness and fabric. The gay and rhythmic jingle of the bells became a melancholy peal, as they heaved ahead, great shoulders quivering with exertion. Another step. Another. It was cold and while motion produced heat, the effort of pulling the sleigh over rocky terrain was wearing. Nikki knew this and felt relieved when he saw first the smoke swirling from the chimney, then the cottage and various outbuildings which comprised the Wayside Inn.

“I could just throw myself down that chimney to get right in among the embers,” said Nikki aloud, utterly fatigued and grateful for respite. Nikki’s legs trembled when he climbed from the sled. The inn keeper emerged from the lodge bundled against the cold and carrying a lantern to light the traveler’s way. “Come in. Come in,” he invited. “I can see you have come a long cold way. Come inside by the fireplace where it is warm. Yes, yes. Bring in the little dog, as well. It is too cold to leave her out in the barn tonight. She is well-behaved, no?” Nikki nodded agreement and was about to speak when the Landlord held up his hand. “ Go inside now. My wife will give you something good to eat. Go in and sit by the fire where you can warm yourself as long as you like. Then you can fall asleep in a bed. You are looking forward to that, no? Let me take your horses to the barn. They will have clean straw beds right next to each other. I will groom them. Be assured they will be warm and dry. And have as good a dinner as yourself. Go in now. Leave everything to me.”

Nikki thanked the kind man and did what he was told. He entered the low kitchen door, half stooping to cross the threshold. Inside the pantry, he stamped the snow from his boots and took off his heavy jacket, the snow-caked mittens and hat and hung them on pegs conveniently near the door which, oh dear, he hadn’t quite closed when he entered, because a gust of wind pushed it open again and a surge of snow blew in. He gave the door a good slam this time and a woman out of view sang out: “That’s how to do it.” Leaning against a quaint three legged stool for balance, Nikki removed his boots and stepped into a pair of felt house slippers left at the door to keep the kitchen clean and feet warm. Then he walked into the kitchen where the innkeeper’s wife was stirring a large pot on the stove. She was a small robust woman with a long grey braid coiled around her head like a crown.

“Come in. Come in,” she said cheerfully. “It’s almost ready.” And when he showed himself, she made a little bow of welcome and respect. “Come. Sit by the fire. Warm you soon will be. Please. Sit. Make yourself homely.” Nikki nearly burst out laughing when she spoke because her phrasing was so very odd, but not wanting to hurt her feelings, he simply smiled and said, “Good evening, Babushka,” which is what people called old women then after the scarves they wore on their heads. She was not wearing one and smiled her welcome

“Come in,” she said again.

“Thank you,” he said, and walked to a chair conveniently close to the cozy fire, sat down, and sighed. Meanwhile, Laika, who could see what a pleasant place this was, went right up to the little woman, wagging her tail, barking hello. Then the Babushka who understood dogs very well, took something out of the steaming pot with her big spoon and blew on it several times before offering it to the hungry animal who in her excitement forgot herself and shook all over to shed the snow still clinging to her coat. Nikki started to apologize for his dog’s behavior, but the old woman just laughed and pointed to the fire. Laika stepped over to the braided rug in front of the hearth which she walked around before stretching out full length to best absorb the heat.

Then the good woman filled a bowl for Nikki and put it on a tray with a big spoon, some rye bread and sour cream. Nikki inhaled the fragrant soup with satisfaction and began to eat. He drank the glass of hard cider his hostess pressed into his hand the moment he set down the spoon. By the time Nikki had eaten, he was half asleep, watching the road furl out before him as it had all day. When the old man, Mr. Orlovsky came in, they introduced themselves properly. Nikki would have roused himself to talk over his prospects, but the Innkeeper, seeing his guest’s fatigue, showed Nikki to his room with a promise they would talk things over in the morning. “Sleep well. Tomorrow we shall see what we shall see and then…we shall see.” Nikki mounted the stairs already in the other world we nightly inhabit and barely heard a word. “Th..you,” he said before he climbed into the bed and was swallowed up in sleep. Laika dozed by the fire, twitching and sighing in her dreams, never once barking.

********************

chapter seven

But the next morning snow enveloped the Wayside Inn and the alabaster world seemed locked in frozen lassitude. When it was full light and the smell of frying onions tickled his nose into wakefulness, Nikki sat up, bumping his head on the attic’s sloping ceiling. His bed was set in a recess of the room. He yawned and stroked his chin, then rubbed the frosted glass of the dormer window and quickly pulled his fingers away…brrrr. He could barely make out the barn across the courtyard. Already the drifting snow was piling up above a man’s boots, steadily falling. A sudden coldness in the pit of his stomach assailed him. How could he get back on his road again if road he could not see?

All at once he saw the vanity of his plan. How blind he had been. With what foresight his father had cautioned him and he had been too stubborn and proud and would not listen. He sighed deeply, hurled himself from the bed and poured a stream of icy water into the ceramic basin from the pitcher provided and rapidly dressed. Usually the morning splash of cold water helped him start each day with firmness of purpose.Today he felt only a great aching disappointment and weariness.

He sat back upon the bed heavily. He had been stopped in his tracks by a force and power larger than his own. He wondered how he should meet with this interruption of his journey…which he should have anticipated. He knew he could not blame an impersonal fate for thwarting him. ”Man proposes. God disposes” was an old proverb he had heard his elders mutter more than once when a small boy listening in on their conversations, curious to learn what they deliberately kept from children. These words occurred to him, but didn’t help. He knew the snare of melancholy that arises from disappointment. He knew he must resist the lure and harm of discouragement. It was late Autumn. Everyone, anyone but an idiot like himself, knew the vagaries of weather during this capricious season.

How could he have been so sure he would find the mildest days and an unobstructed path from one house to the other? But hadn’t others been as sure as he that the fine weather would hold, as it had last year until well past the solstice? Well past. But now it was snowing and that was that. Fearing he would have to return, knowing he could neither go forward nor back, he felt stymied and abashed. How could he face them, having failed?

Laika’s barking interrupted the wallow of his rumination and brought him to his feet. Uncertain how to bear with his predicament, he hastened down the stars to prevent Laika from making a nuisance of herself. At least he could do something useful. But Laika’s barking had stopped and he paused at the kitchen door, considering if he should first go to the barn to attend the horses and appraise his prospects for continuing on, hope against hope. He stood awhile poised at the door, stuck in the spinning wheel of what-ifs and perhapses and all the feckless fuzzledom his thoughts were turning in.

He didn’t quite hear his host’s invitation to the table where breakfast was waiting.

“I said,” said the Innkeeper, ”Come inside and have your breakfast.”

“Have I got dressed yet?” Nikki asked, perplexed.

“I’m on the other side of the wall and do not have a crystal ball,” said Orlovsky, “so I cannot tell. Better ask yourself.”

“Would you like something to eat?” The old woman interrupted before her husband could have some more fun with this muddled lad, in the clutch of befuddlement.

“Good morning, young traveler. I hope you slept well,” said the Babushka. She got up from her place at the table where she was peeling potatoes and took her pot over to the great stove to cook. When she returned, she examined the young man who looked dejected and vexed. Seeing his unsettled demeanor, the old woman kindly admonished him. “Calm yourself,” she said and then laughed. “Come and have something to eat. Sit.”

But the old man cocked his head and looked at Nikki through squinty knowing eyes. He was drawing on a pipe and let a big puff of smoke out through his nose. “How far are you, were you planning to go today and wither?”

“Ah, me,” sighed the erstwhile traveler. “Wither indeed?”

“Withered in doubt, you mean, perhaps? Quick woman, give the boy his food. He’s hungry, for sure, though maybe that is all that’s certain.”

Nikki sat down and she brought him buckwheat pancakes along with jam. Then she poured him a glass of steamy tea from the pot kept warm under layers of hand woven cloth which Nikki thought quite charming, reminding him of home. ”Drink this,” she said. Better you will feel when you eat.” Nikki took the glass in both hands and drank. Immediately he began to revive and he ate his meal, bite by thoughtful bite. As he chewed, he became more settled, less agitated and by the time he finished, he was restored to tranquil good humor. Such simple creatures we are, our bellies cleaved to the earth.

When he had finished, the man extended his hand and asked for his guest’s name. Nikki introduced himself and they bowed in the old way, then shook hands in the new. “You are welcome to weather the storm with us. Stay as long as you like. I’m going to the barn and will see to your horses. No, stay,” he said, when Nikki stood. Laika who had been dozing again, sprung to her feet and stretched. She barked when Orlovsky bundled up and when he opened the door, she barked again and followed him through the door and to the barn.

Nikki turned to Orlovsky’s wife and thanked her for breakfast and for their hospitable lodging. “You are welcome,” she said, “Shall we talk a bit and consider what’s to be done?” Many young men then and even now, I’m sorry to say, would not have deigned to greet a servant who opened a door much less confide in a stranger with whom relations were impersonal and perfunctory. But Nikki didn’t care for such distinctions of rank and script. His family had inherited their egalitarian views from elders who remembered the ideals of the French and American Revolutions, who remembered to think. They had a high regard for universal human dignity and treated everyone with respect.

“Yes,” said Nikki, grateful for her conversation. “I can think of nothing else. My thoughts go round and round like blowing snow and I can’t see three feet in front of me. The storm in my head is as big as the one out there.” She nodded and they both peered through the window and surveyed the winter scene. The snow was coming down, blowing round and round. They watched Orlovsky trudging to the barn. Except that she was bounding, it would have been hard to distinguish Laika from the mounds of snow. It was one of those quiet storms. Hour by hour, the snow falls and the sky is muffled, the outlines of trees and buildings blur, blanketed in snow, until finally the earth is transformed, stilled in perilous loveliness. They sat there a long time gazing, transfixed.

At last, she cleared her throat, as if to make a speech. “My boy,” she said, ”Perhaps you know the ways of fishermen who hindered are by bad weather and can not go to sea. My father in a fishing village lived. He told us how big the sea becomes and wild. Between the swells and troughs, a man in a small boat, even the strongest, even the smartest, can over go and drown.

Nikki looked thoughtful while she spoke. “I see,” said he, in the pause she took while finding her words. “So,” she continued, taking up her knitting. “When to sea, they can not go, they do not idle stand, shaking their fists, moaning or complaining. No. Their nets they mend, firewood chop or bench they build. Maybe who needs their help, a wife…or neighbor.” She winked at him and Nikki nodded, taking her meaning. “You are welcome to stay until onward you may go.”

And so he stayed, making himself useful to the old pair, happy enough to be occupied, making repairs with the old man in the barn and holding skeins of yarn in his outstretched arms for the Babushka who drew the wool from his hands towards herself, winding it into a ball, ready for knitting and crochet. At last there came a break. The storm subsided and there was the road under the hard-pack of snow. Because he knew now that other storms would surely follow, our dreamer resolved to turn back home to family and farm. Next year, he’d leave earlier, arrive earlier and stay to help Vera and the children until winter loosened its grip and he could safely wend his way home in clement weather.

The year after next, on midsummer’s day, he and Tasha were to be wed. He would leave youth and his fierce unreasonable inclinations behind, his energies transmuted into the life of a married man. Ergo, next autumn he must go. And that was that.

********************

chapter eight

No one was really surprised to see him return, though they made an effort to refrain from teasing him, swallowing their smug “I told you so’s.” By the following summer, whether in tavern or bath house, every man in the vicinity, listened to Nikki’s scheme. Those who had kinfolk in the north asked him if he would take along playthings for the children and of course Nikki had agreed. So hammers hammered, saws sawed and fingers flew. How they bustled about every moment they could spare. They carved and whittled, constructed and assembled loved and familiar animals…dogs and horses, cats and cows. Some made fanciful creatures like mermaids and gnomes, others strange or whimsical curiosities like the man in the moon.

And the dolls! Several were soft and made of rags… some large, some small. The potter made a pair of smiling infants out of bisque so convincingly colored, they seemed about to speak. The candle maker made a ballerina out of wax. There were wooden dolls in old fashioned suits of clothing sewn by wives. There were nesting dolls and wooden soldiers with regimental uniforms painstakingly painted upon their sturdy frames. Someone made a kind of Jacob’s ladder with an acrobatic figure that climbed the string. Another made a Jack-in-the-box which popped out a startled Motley Fool. The shoemaker made a marionette with moveable limbs the young puppeteers could manipulate and lose themselves in invention, skit after skit.

There were chess pieces and checkered boards, six sided die, little palettes for mixing paint, and carved boxes to hold paints or buttons and stringing-beads. There were whistles and flutes and even tambourines made of metal, wood and hide. There were toy tops made of wood and one of hammered tin painted with intricate designs in the colors of autumn and spring. As if by magic, the blacksmith forged miniature soldiers and canons for his nephews, and a tiny iron horse and carriage for his niece. How had he conjured these charming replicas so miniscule, precise? You never saw such an array of objects wrought to fascinate, inspire and amuse. The toys were simply splendid, labors of love so cleverly conceived and skillfully made, so ingenious and enchanting, you’d think the villagers possessed by elves and other fairy folk.

All summer and early fall the collection grew, and by the time preparations for the second journey were complete and Nikki ready to depart, the voluminous bag of carefully wrapped and marked gifts bulged and occupied much of the sleigh, leaving scant room to shift about. He and Laika would be cramped. Each night they camped in the open, he’d have to remove the bag to stretch out and sleep. But no matter. He was going to bring happiness to the young ones cherished by neighbors and friends. He felt happy contemplating all that was in his power to bestow.

He and Laika set out as soon as the snow stayed, making a good surface for the runners of the sleigh. It was an unusually early freeze, shortly after the first gusts of Autumn howled and tore the burnished leaves from branch and bough. But he left with heavy heart, worried he wouldn’t succeed. And he hadn’t. The elements prevailed.

The following spring, on the day spring becomes summer, he and Tasha were married. The cousins from the north, Vera, her children, Peter and Elena, and most happily, her husband, Leo, restored to them at last, came to witness the ceremony in the village church hard by the family estate and to feast with them for many days before they journeyed on. The next autumn, he wrote Vera to tell her that what he once intended, his dream, he had relinquished, and she replied with gratitude. “Never mind. It was your wish for us that matters.” However, he knew in his heart that good intentions were no substitute for actual deed.

Nikki became a good husband and father, a prosperous and respected merchant, well liked and admired. He and his wife lived more or less happily ever after. Really, their lives hold little interest, taken up with earning a living, keeping house, raising and educating children, assisting neighbors when their help was needed… same old story.

In his middle years, when his children were grown and everyone called him Nik, he began to fill out the thin outline of a boy into the broad and greater girth of a man and finally, he grew stout. Indeed the pleasures of the table and a life more and more sedentary and indolent with not enough exercise made him exceedingly round. His physique not withstanding, he was still vigorous, so neither he nor anyone else considered his amplitude a deficiency. By the time his grandchildren were crawling over his soft and springy lap, loving to cradle in the soft pillow of his belly, his curly hair had lengthened and grown quite white. He grew a beard and moustache as well, a shimmering silver like his hair.

He may have faded into old age and disappeared as finally we all must, had not a curious and fortuitous thing happened, something that changed the course of his life and perhaps the course of yours and mine as well. One thing leads to another, as a line of dominoes topples, as one ripple pulses to the next. He received a letter from Elena, Vera’s daughter who had children of her own, all she had of family, her only kin at home. Both Leo and Vera perished in an accident he could not bear thinking about, which left a hollow ache he knew would never go away, though life went on…as it always does. There were many cherished people daily present in his life, and if not entirely consoled, he was amply content. Life wasn’t as simple for Elena, on whom he doted as he had her mother. Her brother, Peter, was far away in France where he lived with his wife among her kin, on her family’s vineyard growing, crushing and bottling grapes, famous for their wines. Brother and sister were still close, but from a distance which is not at all the same as closeness in proximity, ongoing conversation and activity. Obviously.

Dear Uncle Nikki,

How can I tell you this? Alexander has been conscripted and we, the children and I, will be here all winter on our own, just as Peter, Mama and I were, in this very house so long ago. Do you remember when Peter and I were very young, you tried to visit and bring us toys and sweets in the middle of winter? When we were trapped inside the house, locked indoors day after day? And so shall we be again this year.

The roads are much better now. Would you not consider coming to see us? It would make the children happy. They have, you know, no-one else, no grandfather, I mean. They want to see you as much as I who miss you, all we have left of Mama. Forgive me, I cannot help it. I simply must ask.

Your loving Elena.

Oh dear, a damsel in distress. Vera’s Elena…laying it on a bit thick… but of course he must go. Not a moment to lose in wavering uncertainty. He was keenly aware that for the first time in years, he was roused from the torpor of his days, the uneventful span that brought him a fair share of satisfaction so muted he hardly noticed. When had he lost track of fierce feeling, the strong sap of childhood and youth? Her letter was a summons that broke the trance and a burst of joy rushed through him, through and through. Ma foie! He had nearly forgotten… purpose, focus, Something to Do.

He called his family together and when he read them Elena’s letter, Tasha didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. Finally she consented. “You may go, but not until I’ve dyed your warmest garments red as before, for it will surely snow and you must be seen.” Looking him straight in the eye, she repeated: “It will surely snow. Good that I have some crimson. Wherever those old clothes may be, they will never fit you now, will they?” She tickled his midsection and his belly shook and shook when he laughed, reminding her of the apple jelly she made that afternoon, the way it shook when the glass jars jiggled.

And while the red garments dried, Nik visited the tavern, the baths, the church and his neighbors’ farms. Men still remembered the folly of his youth, but were excited by the idea again. They searched for the toys they made with such enthusiasm a long time ago, that somehow or other had never been sent. Some found time to make new ones. Nik collected their toys and treasures and filled a large sack to the brim, presents for kindred living more or less along his path, with whom he would stay on cold and starless nights many weeks ahead. The sleigh was soon made ready and Nik prepared to resume his quest.

Laikas, as you know, do not live forever. And many Laikas had come and gone over the intervening years. Nik had no second thoughts about taking their current Laika with him, a dog who was no longer a puppy, though still young and strong. This Laika was not much of a barker and Nik sometimes called him Niet Laika, not a barker, and Laika wagged his tail or thumped it on the carpet if he happened to be stretched out on the floor, happy to be noticed, whatever he was called. He sprang into the sleigh with his master, a tight squeeze, but everyone was jolly and everything just right. And so with many hugs and fond farewells, wrapped in red wool and trimmed with ermine fur for added warmth, Nik and his traveling companions, Niet-Laika, the dog, Lauris and Floris, the horses, set off to bring joy to housebound children, stifled in the drear of winter, in the far away country to the north.

********************

chapter nine

There were more inns now at regular intervals and the air was dry and crisp. The days were long and tedious, but there was nothing to break the monotony and plodding of the journey. Nik made sure the horses were well fed and rested. He and Laika fared well enough, happy to exchange their seats on the rug- covered hardwood bench in the confining sleigh for a soft, more comfortable bed to stretch out in, every night.

Nik took up singing to pass the time, songs from long ago, the ones Tasha played on her balalaika or spinet and which they often sang together to pass the time, harmonizing their not exactly tuneful voices. No one is perfect. Singing made him nostalgic for his wife and thinking of her, he felt less lonely. Laika occasionally joined in with his doggy howl, but mainly he thumped his tail or ran along side of the sleigh for exercise where the singing was not directly in his ear.

They passed field upon field where the hardworking Muzhiks were bent over, scything and gleaning the last of the long grasses. Soon such scenes of hay making grew rare as they moved through time and space, progressing ever northward, step by step. The days grew shorter, the nights longer, the skies darkening well before dusk in the dim grey cloud-wrapped overcast. The air grew heavy with moisture. Then it rained. Then it snowed, flakes descending when the temperature dropped. They had left the shelter of village and valley and were traveling through the high forests of oak, aspen and birch.

Inevitably, they came to the long broad river Nikki knew they must cross to get on. They were deflected from their course to find a bridge that spanned the streaming water. The river was not yet frozen, so there was nothing else to do. This meant delay and cost them several days. When finally they found the bridge, Nik got out and led the pair across the wooden structure, standing close to them so they wouldn’t startle at the loud and hollow clatter of their hooves. And when they once again set foot, paw and hoof on Terra Firma, Nik was beaming, overjoyed. Crossing the wide river was a milestone, a marker which told him they were near their journey’s end, almost there.

But there were still who knows how many days to go and the lowering skies threatened weather that might force them to stop. Nik was sure they’d reach the next roadhouse by nightfall and he spoke to the valiant horses, whispering in their ears, urging them to exert themselves for more speed. But it began to snow harder and the earth turned white, covered in the kind of snow that mounds and transforms the landscape.

********************

chapter ten

Calamity followed. I am sorry to say so, but there it is. How it happened exactly, Nik was never able to recollect. It happened. Just like that. The horses were trotting as usual and suddenly, out of nowhere, there was, there must have been, an impediment, maybe a fallen limb buried under the accumulating snow. The horses lurched and they both lost their footing. There is nothing more terrible than horses’ screams or the terror in their eyes. They tried to remain upright, but in the ensuing tumult, Nik saw one rear up, eyes wide, lunging, plunging, then foundering. The sleigh overturned, taking the horses with it, slipping over an icy embankment where it rolled before falling on its side in a tangled mess. Floris fell on top of Lauris, crushing his ribs with the weight and impact of her fall. Nik and Laika were both thrown from the sleigh. That was all he remembered before everything went black.

When he came to, disaster surrounded him. Floris was dead, pierced by a sharp fragment of splintered wood from the damaged sleigh. Lauris was breathing, but with difficulty, terrible gurgling coming from his throat. Nik was stunned. Was this the end, not just of journey, but of life itself? Better to go down on a noble errand, than to stay alive in meaningless felicity and ease, he thought. But this was small comfort. He wanted to live.

There was nothing he could do for Floris and really nothing for Lauris close to the gate of the next world, soon to pass through. For an instant, he thought he saw Laika bounding away from the sleigh, but he couldn’t be sure. He called and called, but there was no answer. Steppe Hounds are nearly the color of a snowy landscape. It would be impossible to see him.

It was almost dark. Nik knew he would freeze if he did nothing. He thanked the deceased horse for all her efforts and wedged himself between the living and the dead for the remaining warmth of their bodies to stay alive, regaining strength he needed to collect wood and build a fire, to keep the fire going while he gathered his wits and pondered what to do, if there was anything to do. It was all too much and Nik couldn’t stay awake. He slept and slept until the lid of night shuttered and the eye of day blinked open. He awoke, body aching and miserable. He was cold. He must gather wood.

And he did, walking stiffly, asking each part of his body if it were still able to move. Everything worked. He got a good blaze going and stayed close to the fire to dry his soaking clothing. When he had dried a bit, he gathered wood to feed the fire, then rummaged among the muddled provisions for something to eat. He found the hourglass, by some fortunate chance unbroken, and smiling grimly, he turned it upside down and watched the granular sand trickle through the neck.

And so he lived for several days, eating dried meat and fish, hard biscuits and dried fruit. He drank water and the remaining kvass. He was unable to right the sleigh, but he made a den for himself at night inside the sleigh on its side, burrowing under every blanket and rug, managing to stay alive for one more bleak and cold day, unable to do much else.

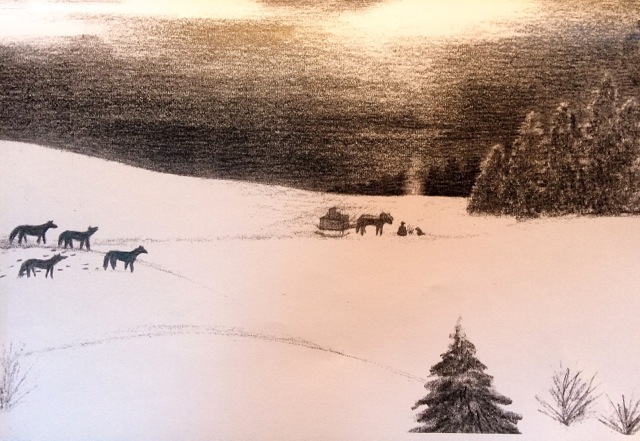

Then the wolves came. Nik laughed when he saw them crouching and slouching closer and closer. ”Be patient, you curs. You’ll have me soon enough. Maybe. But not today. Better yet, go away.” One grey form crept close but Nik chased it away with a flaming torch and kept the growling pack at bay by building up the blazing fire where he squatted hour upon hour, standing and walking about, close to the fire to regain sensation in his stiffening limbs. When he couldn’t see their eyes following him, he sensed their watchful presence. A waking nightmare. More I will not say.

And there he would have expired had not a benevolent providence and an intelligent loyal dog intervened, had not the Samoyed trader come along with his big dogs and sledge heavily laden with trade goods, conveyed by caribou. Laika found the man or the man, Laika. No matter. It might not have happened, for the hound was nearly inconspicuous. But the trader’s dogs picked up the scent and wouldn’t stop their yelping until the man stopped to investigate.

Laika barked for once in his life, barked and barked. Then he trotted ahead and came back and barked again, repeating the figure until the trader followed him to the place of disaster, to Nik and the wreck of the sleigh. His tail wagging feebly, he walked around Nik and collapsed, energy and life force spent. He was panting, his tongue hanging out. Nik bent down and put his hand on the dog’s heaving body and Laika breathed his last. Nik stayed beside him for a while in silence, then stood to meet the man his dog had brought to rescue him before he ceased to be.

The Samoyed lived among many people and like the Lapps and Finns, was well acquainted with this part of the world. As is so often the case with traders, he was fluent in many languages. So when he found our hero by the fire and saw that he was not discernibly hurt, he spoke in several dialects until he made himself understood. “What happened?” he asked,“ and Nik told him everything, drinking the plum brandy the trader handed him. He relayed the shattering details of catastrophe, and also told his listener about his mission, yet to be fulfilled. The man, Anu, nodded when Nik spoke and understood the survivor’s grief. Anu reached out to put his hand on Nik’s arm.

“I know a colony of farming people nearby,” he said. “They will be glad to have you stay with them. You may rest and recover your strength while I deliver my goods. I’ll return in a few weeks. By then, you will know what to do, whether to go on…really only a short distance once you know the way, which, lucky for you, I do. If you prefer, you can return home. Either way, I’ll help you. These caribou are well suited for the winter and know how to move in snow.

Then Anu asked Nik if there was anything he wanted to take with him and Nik pointed to the bag of toys still inside the sleigh. Anu retrieved and stowed it on his own sledge for safe keeping against the elements and scavenger beasts. Nik wrapped Laika in one of his fur rugs and the Samoyed placed the body high in a nearby tree as Nik asked of him. Then the good man helped Nik into the sledge. Although shaken and weak, he had the presence of mind to thank the man who was delivering him to safety.

********************

chapter eleven

Anu was right about the people of the colony. Harvest was over, all the labors of summer were, and this was the time of rest. They welcomed Nik and took him to the communal bath so he could cleanse himself and rejuvenate in the tonic mineral water. One of the women took his clothes away to mend and clean. She promised to find him some warm garb to wear in the meantime. She was certain there was someone with garments big enough, who would not be loath to share.

The bania was a large and well made building with pools to soak in and a small lodge, like a sauna, to sweat in. But before they went in, Nik’s hosts told him to make an offering to the Bannik. First he made the sign of the cross as people did, and next wished his companions a wholesome bath. They saluted the Bannik and Nik in turn. He stayed in the water a long time, long enough for his skin to pucker. Soaking in the hot water made him drowsy and when his fellow bathers saw him nod and drift into sleep, they pulled him out, gave him a thick towel to dry himself, and reminded him to thank the spirit of the bath. He crossed himself again and left a little bit of soap for the exacting spirit, wishing it well.

Bathing was not only ritual, but a way of life for these people and Nik soaked daily in the heated pool, never forgetting to thank the spirit. Not wanting to annoy the Bannik, he refrained from singing though he might have been tempted to hum in the upsweep of mood. He was grateful to be alive, grateful to have a spirit to thank, however strange the custom of appeasing appeared to a modern man like himself.

By the time Anu returned, Nik was ready to resume the journey. “But,” he told Anu, “I have no horses to pull my sleigh. How shall I go on?” “I have an idea,” said Anu. “Let’s return to your sleigh to see what can be salvaged. Then we can see what is possible.” Nik dreaded the ghastly scene but knew he had to face it if he were to salvage the sleigh and go on. His bag of presents was still on the trader’s sledge and his own clothes, a little worn now but still serviceable, had been returned by the woman who first met him when he arrived, the red and white garments cleaned and neatly mended. He put them on and felt like himself again. He thanked the colonists for their kindness, wishing he could repay them for their hospitality. He would find a way. In the summertime, he’d come back and bring them dates and other sweetmeats from the south.

The snow was now settled and though cold, the wind had died down and traveling was nearly effortless. The little reindeer stepped so gracefully and sympathetically with one another and the ride over the hilly terrain was made smooth and easy by their nimble feet. And so they made good progress. When they came upon the scene of carnage, the sight of disaster was chilling. Wolves and other predators had fed on the remains. And while this was only to be expected, the bare bones exposed made a ghastly sight, like a scene in a medieval painting. Nik and Anu looked at one another. What could they say? Anu jumped to the ground ready to act. “Let’s see if we can move the sleigh away from the horses.”

Once done, they untangled the tack. Then it was not so difficult to lift the sleigh upright. The runners were in tact and other damages easily repaired. The sleigh was still functional, vehicle and conveyance in working order. That was something. Anu went back to his sledge and transferred the sack of toys to the sleigh, then went back for the rugs and fur blankets the colonists had given Nik along with food for many days. Meanwhile, Nik raked through the debris and retrieved what unbroken possessions he could find. He stared at Anu, not fully grasping what was next and how. “Now what?” he asked Anu, who for answer, released eight caribou from the team that pulled his sledge. Nik watched them approaching and understood. He smiled and sighed, then laughed so hard his belly shook and tears formed in the corners of his eyes. The men gathered up tack and harness complete with jingling bells and fitted the charming, sure-footed reindeer to the sleigh. And so… the journey resumed.

********************

chapter twelve

Anu inscribed a meticulous chart on thick paper with his fountain pen, the latest invention. Then he showed Nik how to read his map. When he was satisfied that Nik had understood, he assured him that the last leg of the journey would be brief, if the weather held and he followed directions precisely. Nik promised he would and after he placed the map in his pocket for safe keeping, he reached into the large bag and brought out Vera’s hourglass.

He meant to bring it to Elena, but he had changed his mind. Instead, he gave it to his new friend and guide, the man who delivered him from a certain death not only to thank him for saving his life, but for all the generosity the Samoyed had bestowed upon himself, a complete stranger, as well. Nik was moved by Anu’s irrational kindness and while he could never repay him in kind nor in full, he wanted to give his benefactor a worthy gift. Anu liked it very much which made Nik happy. Then they reviewed the route, bowed to one another and said goodbye. Taking up the reins, Nik spoke softly to the reindeer, asking them to start, and when they pricked their ears and picked up speed, the strings of silver bells resounded. How they rolled and trilled and chimed!

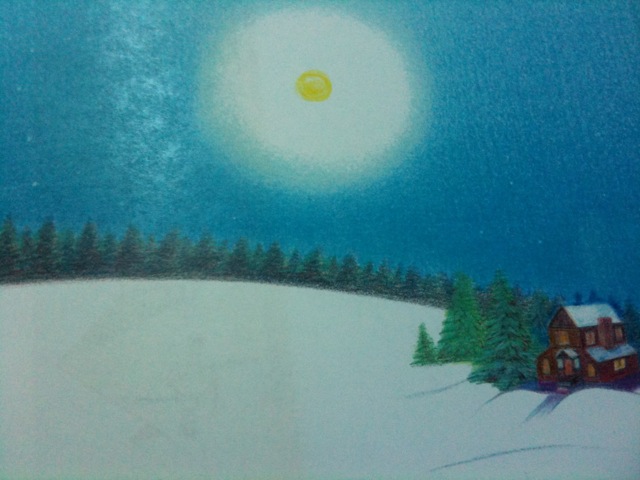

The first evening, Nik stayed with the kin of the blacksmith, and pulled presents for the children from his sack. Night after night, he stopped and fed the reindeer and accepted the hospitality of his neighbors’ kin. Night after night, the bag grew smaller until finally he attained his cousin’s manor. He arrived after nightfall in the light of a full

moon shining on the crisp and deep-lain snow. When he stepped down from the sleigh, he thanked the Spirit of the Bath again. The little reindeer shook their heads and the singing bells rang merrily. Then Nic’s boots crunched on the surface of the snow as he walked to the big front door. At first quietly, then loudly he knocked and knocked, but no one heard him there. No one came to the door to let him in. Undaunted, he walked to the side of the house and spryly mounted the steps that led to the roof. He picked up a loose brick he found there and dropped it down the chimney. To his satisfaction, it crashed loudly to the stone floor of the hearth. Such a noise it made, such a clatter! Then he climbed down and went back to the front door.

The disturbance woke Elena who came to the door to see who was there and what was wrong. When she saw who it was, she put her arm through his and drew him inside. Then, after much tearful embracing, she let him go to settle the reindeer for the night and bring in the toys and sweets he had brought for the children. When he returned, he stepped inside and removed his boots. Then he padded to the sitting room in his stockings where a fire was blazing in the hearth.

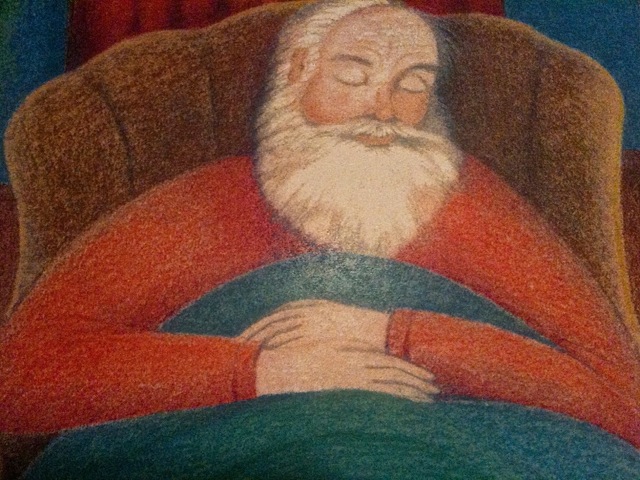

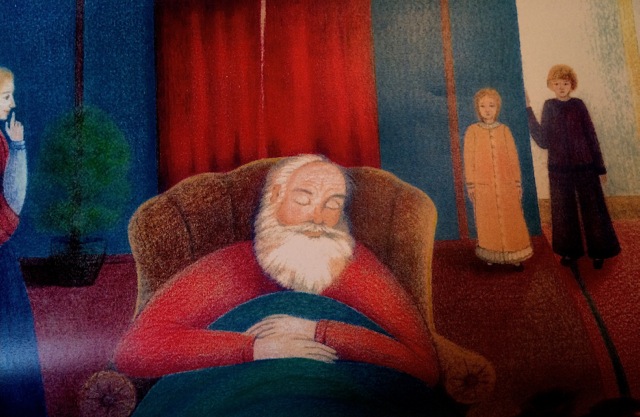

He had succeeded. He was finally and really there. It was just after Solstice. Elena brought him a fresh pair of stockings to warm his feet and a blanket for his lap and when she left to bring him warm milk and gingerbread, he took off his large stockings and put them aside. But instead of putting them on, he stuffed the stockings Elena had brought him with the toys and sacks of sweets. Looking around for a good place to display them, he settled on the wooden mantle over the fireplace where he suspended the overflowing footgear. The little ones would find them there in the morning. He placed his finger beside his nose to help him remember something he wanted to say to Elena, something that eluded him, just out of reach. But he was so very weary that in the twinkling of an eye, he fell fast asleep in the armchair by the fire, still in his red woolen clothing where the children found him the next morning. They opened their small arms and large hearts to welcome him, this jolly old man who was their very own kinsman, their own Father Christmas, their own sainted Nic.

********************

chapter the last

Nik returned to his Tasha in the spring time and dwelled with her a very long time… as happily as any couple can… living to be a venerable old man. And while not exactly balmy nor entirely predictable, he said what he meant, meant what he said and thoroughly enjoyed himself. In his own time, his quest became legend. In fact, he was so honored and revered, some people hallowed his name.

Some say that after their children had grown and taken their children to the four corners of the earth, emigrating to this land and that, Nik and Tasha removed from their estate in the south to join their cousins in the north, as far away, they say, as the North Pole. Of course, some of the particulars of his famous journey were exaggerated or altered by the usual means of rumor and gossip, but not by much. Not really. You know the rest, dear children. Happy Christmas. And to all peace and good will and good night.

The end.